Entering permanent liminality: Why our anxiety over ambiguity is getting worse

Humans have an inherent need to classify, to put people and things into boxes. Our brains just aren’t big enough to deal with the complexity of the world, and so we must simplify it into categories (this is part of the well-known concept of bounded rationality).

Everyone and everything has their place. We organise people into genders, nationalities, education level, generations, political parties. We act according to defined social norms. The world is divided according to territories, living/non-living, shapes, colours. This continual classification makes life simple, it keeps us in control.

We hate ambiguity and uncertainty. In many cultures, things which fall out of categories are seen as ‘dirty’, ‘out of place’, and excluded from society. Some anthropologists have argued this inherent need to classify explains food prohibitions in certain cultures and religions (animals which don’t fit into categories are seen as ‘dirty’ and therefore can’t be eaten). This is one reason why certain groups feel so uncomfortable about new cultures, ideas, genders. Many studies in psychology too, have revealed our deep intolerance of ambiguity and uncertainty.

Continual classification makes life simple, it keeps us in control […] We hate ambiguity and uncertainty.

But there’s one moment where, across all cultures, we accept things to be vague, unfixed, upside down and topsy turvy. It’s the moment when we transition from one of these defined, classified states to another. Anthropologists who study rites of passage (a change of state, age, social position e.g. child to adult, single to married, woman to mother etc.) call it “liminality”.

Liminality is the defining period of ‘limbo’ in a rite of passage. It’s a specific moment between “separation” from previous state and “reaggregation” into new state, where, across cultures, we observe temporary ambiguity.

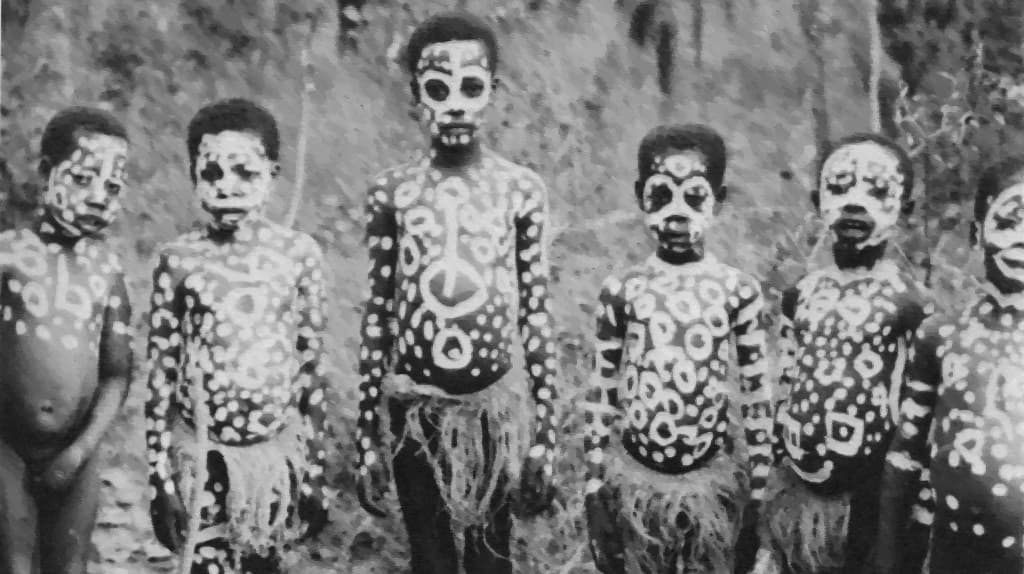

For example, in Zambia, young Ndembu men (as described by Turner, 1969) undergoing initiation or puberty rites may be represented as possessing nothing, and may be disguised as monsters, wear only a strip of clothing or be completely naked. As ‘liminal beings’, they have no status or property (as clothing indicates rank, role or position in the kinship system).

In India, pregnant brahman women (who are transitioning to the status of ‘mother’) are placed in isolation from their family group, to reflect their socially/physiologically abnormal condition, and considered impure or potentially dangerous (Van Gennep, 1909).

Anthropologists say these periods help societies make sense of the change, and make reintegration easier – because change is disturbing. But we undergo this because the new identities are required for people and societies to function.

We have liminality in western cultures too: before getting married, ‘stags’ and ‘hens’ are given lap dances (not by their partners), dress outrageously and eat ridiculously-shaped food. Before becoming mothers, pregnant women are allowed and given social permission to be publicly irate, demand specific food… Ricky Gervais’ recent Netflix show Afterlife nicely displays the (short) period of grace granted to people going through grief, in which they can behave rudely and stay in bed for days.

At a societal level, liminal periods are sudden events which disrupt normal hierarchies and social distinctions – an invasion, a natural disaster, a revolution, a war. In the period after 9/11, New York entered a liminal period. Many of spoke racial divides disappearing, people opening their homes, serving free meals and supporting each other.

These liminal periods help us transition, they are essential to personal and societal development. And they are effective because they are contained, short, they have an end point.

Liminal periods help us transition, they are essential to personal and societal development […] but they have to be contained

But in our fast-paced, ever changing world, this is no longer the case.

The exponential socio-cultural change (more detail this in our last article) and digital progress we have witnessed in the last decades is making it hard to contain and put an end to liminality. The world is changing too fast. There is no ‘fixed state’ for us to return to. We don’t know what the next state looks like. So the in-between period doesn’t end.

Imagine going away on a trip, coming back feeling changed and transformed, but the home you’ve returned to isn’t home anymore. The context for our new identities is changing beneath our feet.

This is what Sociologist of the Imaginary, Michaël Dandrieux describes his Ted Talk on the world in crisis:

“We’ve grown up in a world in crisis. Which is incredibly suspicious when you think about it because the principle of the crisis is that it is a peak. It’s a moment, you pass it, and then you do something else. And yet, our age has invented the permanent crisis.”

(and he goes on to brilliantly dissect the list of crises on Wikipedia – existential crisis, masculinity crisis, economic crisis, midlife crisis, political crisis, housing crisis, demographic crisis, climate crisis … and the list goes on)

Returning to ‘normal’ (or to a new identity) after a period of liminality or crisis is what supports our personal and societal development. But these never-ending and intertwined crises mean we are struggling to return and anchor down. We are entering permanent liminality. And, we react as humans have always reacted when they cannot organise and classify: we are uncomfortable, we lose control. No wonder everyone is talking about the age of anxiety.

Never ending and intertwined crises mean we are struggling to anchor down. We are entering permanent liminality.

We don’t yet know what the impacts of this will be on our development – especially for new generations. The transition from childhood to adulthood is undoubtedly globalising and changing.

How do young people transition and mark these changes when technology is evolving faster than they are? What are the new rites of passage? How do they connect to a continually changing culture? And how do we identify, create, and leverage these new rites of passage?